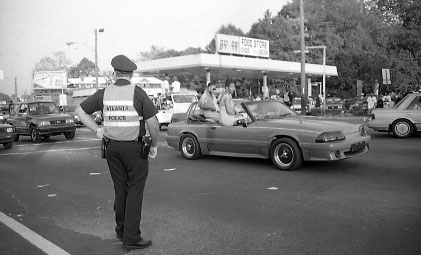

PHOTOGRAPH BY AP IMAGES

An oral history with Kasim Reed, Sam Massell, Jermaine Dupri, Dallas Austin, Eldrin Bell, Luther “Uncle Luke” Campbell, Sharon Toomer, Ryan Cameron, and many more

Chapter I. The Innocent Origins

It all started in the spring of 1983 with a picnic organized by students attending the Atlanta University Center. As at other historically black colleges and universities, AUC was home to “state clubs” made up of students with common home states. The clubs held social events during the school year and served as pre-Facebook clearinghouses for shared rides home. That spring, members of the DC Metro club threw a picnic in Piedmont Park for students who found themselves stuck on campus over spring break. It was a simple event—sandwiches, coolers, boom boxes, that sort of thing, recalls Sharon Toomer, then a Spelman College freshman and one of the organizers. “A lot of us came by bus; no one had cars back then,” she says of the gathering in the field at the corner of 10th Street and Monroe Drive. In those days, Piedmont Park was shabby, the picnic area little more than a vacant lot.

Marcellus Barksdale came to Morehouse as a history professor in 1977 and still teaches history and African American studies. At that time, the “state clubs” were real popular. The DC Metro Club was made up of students from Spelman and Morehouse who were from Washington, Virginia, and Maryland.

Sharon Toomer now lives in Brooklyn and is the publisher of BlackandBrownNews.com.That year, we had a theme called “the Freak.” We had the “Freak Dance,” which was close to the holidays. It was really around the dance at the time, which was “Le Freak,” the Chic song. Rick James and all that just became our theme.

Marcellus Barksdale: There was that song, “Superfreak.” And [the event name] was like, “This is where we were going to be able to get freaky.”

Sharon Toomer: It was a student called Rico Brown who suggested, “Let’s call it Freaknic,” putting together picnic and freak.

PHOTOGRAPH BY SHELIA TURNER

Over the years, the spelling morphed into Freaknik and the event’s timing shifted from spring break—usually in early March—to the “reading week” period before final exams (generally the third weekend in April). As talk of Freaknik spread, it drew students from far beyond the AUC—and a fair share of non-students. For several years, the party hopscotched from park to park on the Westside.

Marcellus Barksdale: They had a big picnic at John White Park on Cascade Road. Nobody was counting heads, but it was a large turnout; I’d say a good 5,000. People brought their boom boxes. They brought their grills, their blankets, and, of course, their coolers. It was a beautiful occasion.

Kasim Reed is mayor of Atlanta. He grew up here and attended Howard University, where, as a college freshman in 1988, he came home to attend Freaknik (though he’d also attended while in high school). When Freaknik started, my brothers were in college. Everyone who’s honest of our generation had some experience with it. When I went it was still cool—and primarily students.

Edward Simpson graduated from Creekside High School in 1995. He works a technical writer and lives in Atlanta. Let’s be very clear: No, my mother did not know where I was going or what I was up to! She would’ve had a heart attack. I would tell her I was going out to a party or hanging out with friends. My older brother was with me, so it was never a big deal as long as I was with him. The West End was somewhere close by that we could get to and still make it home in time for our curfew.

Kwanza Hall has served on Atlanta City Council since 2006. He first attended Freaknik while attending Benjamin E. Mays High School, where he graduated in 1989. Later, as a student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Hall returned to Atlanta to attend Freaknik. I only caught wind of it because I was in Mr. Butler’s art class. I was a freshman, but the art class, it was all seniors. If you were around them, you knew what they were doing. When I heard they were going places, I would go, too. You had teachers whose children were there. It was the chatter of the big brothers and big sisters of my classmates. Someone who might’ve just graduated tells the seniors, “Look at what we’re doing! We go to this thing called Freaknik!”

Derrick Boazman attended Morris Brown College from 1986 to 1990 and was involved in student government. He served on Atlanta City Council from 1997 to 2004 and currently hosts a radio show on WOAK. It was at Washington Park for a couple of years, and then it got too big. By the time I was student government president in 1988, it was beginning to reach levels where tens of thousands of people were coming. It mushroomed into something bigger than something anyone could recall or manage. Freaknik came full circle and back to Piedmont Park.

Chapter II. From Picnic to Phenomenon

Freaknik evolved from picnic to party to long weekend of concerts and cruising through Atlanta’s dogwood-shaded streets. Buzz rippled through the campuses of historically black colleges and universities, luring students who road-tripped to Atlanta for all the reasons college students congregate anywhere: music, dancing, drinking, love, lust, and the chance to just hang out. In Atlanta—with its black political and business leaders and rich history—they found a welcoming environment. “Growing up in a place like the San Francisco Bay Area, where mainstream white middle-class culture pervades, the only understanding you had of college spring break came through a white filter,” recalls Ayanna Brown, who attended Tuskegee University in the early 1990s. An April pilgrimage to Atlanta proved “you could be black and academic and have fun—but it happened not at the beach but smack dab in the middle of the city,” says Brown, now a professor of education at Elmhurst College in Chicago. As Freaknik grew, weekend events spilled out from Piedmont Park and into clubs and concert venues around town, attracting performers and promoters. But for most attendees, the attraction was not so much going to events as getting there.

Jermaine Dupri grew up in Atlanta and still lives here. He launched his record label, So So Def, in 1993. I was 16 the year I became aware of Freaknik. I drove into the traffic not knowing what it was. I was driving to a specific nightclub; I think it was Club XS in Decatur. It was like eight or nine in the evening. This was like one of the first years when it got bigger. They were in the parking lot. I was just like, “Why is it so many people over here?”

PHOTOGRAPH BY SHELIA TURNER

Chris Williams attended Frederick Douglass High School in Atlanta and from 1995 to 1999 was a student at Tuskegee University, a two-hour drive from Atlanta. He (officially) attended his first Freaknik as a college freshman. Driving downtown on I-75, there were droves of girls driving down the expressway trying to signal you to pull over. It was just wild.

Ayanna Brown: My freshman year, it was like this weekend where everybody was just gone. By the time my sophomore year rolls around, the buzz around campus was, “You better get ready for Freaknik!” There was never a flyer posted, but we all knew when it was. For us driving from Tuskegee, the most interesting thing about it was the massive exodus of our college campus. We would typically leave early Friday morning. One of the things that really resonated as we would be driving to Atlanta through Columbus was that traffic.

Jermaine Dupri: I had a motorcycle just for Freaknik, just so I could ride around in the streets. You wanted to be in it. I had to have a convertible during Freaknik. I wanted to be seen, but I wanted to see everybody at the same time. It was the beginning of “flexing,” in every kind of way. The birth of riding around with your system blasting, with TVs in your car. All of that stuff came from people wanting to be seen at Freaknik.

Ayanna Brown: The highlight of Freaknik was getting stuck in traffic. It was in traffic that music got louder; people started talking to one another, asking, “Where are you from?”

Chris Williams: Girls were flashing. You got folks trying to get it on in the car. I remember me and three of my homeboys with me driving down I-85 approaching the baseball stadium, and some girls from North Carolina were honking their horn trying to get us to pull over. We pulled over at a gas station, exchanged numbers, and ended up hooking up that night! It was a wild time.

Luther “Uncle Luke” Campbell was a founding member of Miami-based 2 Live Crew and originator of the hip-hop genre known as “bass music” that became the de facto soundtrack of Freaknik. I heard about Freaknik when it first kind of started up, when people used to tell me that the students were going. They had this thing out in the parks. As the years went on, it became a big bass thing. Then I started getting booked to do concerts in the park and then shows at the clubs.

Jermaine Dupri: This was pre-Twitter and all of that. If you’re from a different city, you’re trying to figure out how to get your music heard in a city like Atlanta. My strategy was to make sure you saw and heard our music. So So Def as the soundtrack of Freaknik—that was my goal.

Chapter III. Freaknik Peaks

From hundreds to thousands to tens of thousands, Freaknik grew, but during its first decade, almost all white Atlantans—and many black Atlantans over the age of 40—were oblivious. Then came Freaknik 1993. That April, 100,000 students converged on the city—triple the number predicted by police chief Eldrin Bell. Gridlock stretched from Cascade to Collier Road. While trapped commuters seethed at the standstill, students got out of their vehicles and danced in the street. All weekend long, the party rolled from Piedmont Park to Peachtree Street to Lakewood to the West End, blocking residents in their homes and bringing business to a halt.

Eldrin Bell: We were overwhelmed by the numbers. The streets were full. The venues were full. The hotels were full. Everything was full. Where in America had we seen, prior to this, that number of African American youth in one place? Nowhere.

PHOTOGRAPH BY SHELIA TURNER

Ryan Cameron was a DJ at V-103 and now hosts a morning show on the station. I would get into the metro helicopter and tell people where it was most crowded and where they should avoid. But instead of avoiding those areas, more people would come!

Deputy Chief Joe Spillane is a 27-year veteran of the Atlanta Police Department. In the 1990s, he patrolled and later supervised Zone 5 in downtown Atlanta. The first year I worked, 1993, I was at Peachtree and Ralph McGill with three other people. Our job was to try to keep the intersections from gridlocking because you had so much traffic in the hotel district going up towards Buckhead. People would just stay on Peachtree and go through the light and block the whole intersection.

Doug Monroe covered Freaknik for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution during the 1990s. He wrote the “Monroe Drive” traffic column. The “first year,” 1993, took everybody by surprise. I interviewed people from all over—even more than the South. I think people came down from New York. It was just everywhere! I wasn’t aware that it existed on a smaller scale before.

Kim Hill lived in Midtown during the 1993 and 1994 Freakniks. The first year, I had family visiting from out of town. We had gone out shopping. It took me from two until seven to get from Lenox Square to Piedmont Park. It wasn’t until I got home and turned on the evening news that I found out what was going on. Once we got back to the apartment, we couldn’t leave for two days.

Joe Spillane: My wife is a lieutenant. She worked Freaknik at the corner of Spring and 14th as an officer. She was talking to someone and leaned into their car, and they drug her across the intersection. She ended up halfway under a car on the other side. She was not injured. But there was so much going on … Of course, they put in a call to help, but the guy got away because there was so much traffic. He was able to get on the interstate and get out of there before he was caught.

PHOTOGRAPH BY SHELIA TURNER

Charlie Harper lived in West Midtown from 1993 to 1997. He currently lives in Marietta and is the founder of the political website Peach Pundit. I’d never heard of Freaknik; I grew up in suburban Atlanta. I was on a blind date going to a wedding. We just got caught in traffic and had no idea why. After the first year, it was like other big events: If you’re not going to be in the middle of it, just get out of the way. I remember thinking, “Why would anyone ever come to Atlanta for spring break when you could be at a beach in four hours?”

Patti Puckett Ghezzi was an Atlanta-Journal Constitution reporter and lived in Midtown in the early 1990s. I asked a young woman perched on a shiny car what was going on and she said “Freaknik!” When I looked confused, she kindly translated, “black college spring break.” I holed up in my apartment and read all weekend.

Eldrin Bell: Mainly, they just wanted to parade up and down the street, and we allowed a portion of that. Now, a number of business leaders disagreed. I’m not sorry that I did allow it. My message was, “Atlanta is a city you can come to. All I want you to do is behave.”

Patti Puckett Ghezzi: For the next week at the AJC, I fielded phone calls from angry Midtown residents. I thought they were cranky and lame.

Doug Monroe: It was a sudden event that came out of the blue, and it’s almost like that ice storm a year ago. It just: Boom! Shut down the traffic. Traffic is just such a big part of Atlanta. When the traffic shuts down, everything shuts down.

As complaints about rowdy behavior raged, then–city council member and mayoral candidate Bill Campbell defended the college kids, saying students he observed were “as innocent as those in Beach Blanket Bingo.” Campbell said with better policing and planning, he would “certainly welcome them back.” But in April 1994, just months after his inauguration and with the Olympics barely two years away, Campbell faced pressure on all fronts. If Atlanta couldn’t handle 100,000 college students over a long weekend, how would it host a million international guests over two weeks? And the city that promoted its civil rights legacy found itself in an internal dispute that split along racial lines—black college students versus white home and business owners—as well as across a generational divide.

Angelo Fuster held positions in the administrations of three mayors: Maynard Jackson, Andrew Young, and Bill Campbell. He resigned in early 1996 as the chief of marketing and communications in the first Campbell administration and now owns Angelo Fuster & Associates, a political and public affairs consulting firm. The concern in political circles was that some in the black community would perceive any measures that restricted Freaknik or discouraged it as City Hall doing what the white folks wanted. That was never discussed, but it was part of a concern.

Sam Massell is president of the Buckhead Coalition, which he founded in 1988. He was Atlanta mayor from 1970 to 1974. We had come a long way in race relations on a one-on-one basis: sitting together at baseball games, working together in businesses. But nobody had seen a crowd like that, a mob scene. People panic with mobs. It was the newness of it, the fact that it was different.

Eldrin Bell: Who owns businesses downtown? Mostly white people. But any complaints were about behavior. I didn’t take that to mean, “We don’t like them here just because they’re black.” I saw it as acceptable versus unacceptable behavior, rather than black versus white.

Ed Gibson lived in Ansley Park in the mid-1990s. My thought was that these kids were exactly like me and my peers back in the day, at Myrtle Beach and in Florida—with different music and less sunburn. Frankly, I wasn’t offended or bothered; it was another phenomenon that makes living in the city so rich.

Sonia Murray works at V-103 and covered Freaknik for the Atlanta Journal-Constitutionwhere she worked as music critic in the 1990s. Beaches aren’t always a black person thing. But hanging out in your car, for a lot of black people, is. It was rarely people that were in college that I ever interviewed. These were people who were working and saving their money, wanting to hang out. It was more like people right out of college. Where would you go to party if you lived in Augusta? Memphis? Tallahassee? Where would you see that many people in one place? What is the equivalent now? Atlanta felt like a black mecca during Freaknik. All kinds of people, all kinds of parties.

Kim Hill: Some people may feel that it was a black thing, but I wouldn’t want 200,000 white kids behaving that way and wreaking that kind of havoc. It was too much in too condensed of a place.

Doug Monroe: I had a telephone call line [at the newspaper] and whenever I wrote anything about it at all, I would get real angry calls with people either calling me an apologist for Freaknik or a racist. It was also a very tense racial issue, I think, because you had the African American students having fun and everybody else wanting to go about their business. It really broke down along racial lines and was quite bitter.

The video for Luther Campbell’s 1993 hit “Work It Out” featured Freaknik 1993 (check out the 0:51 mark) and concert footage shot in Atlanta.

As Freaknik 1994 approached, civic leaders decided to deal with the weekend by changing it. Downtown businesses tried to raise funds for the Atlanta Black College Spring Break Celebration, or as the newspaper called it, “The Party Formerly Known as Freaknik.” This did not fully take off, nor did Freakfest ’94, another structured event. In advance of the students’ arrival, Campbell assured business owners and intown residents that the city would crack down. City Council approved $175,000 for security and cleanup.

But Freaknik’s place in HBCU culture had grown even larger, thanks to media hype of the 1993 gridlock and rap videos such as Luther Campbell’s 1993 “Work It Out,” which included footage from Freaknik 1993 and a concert at Lakewood Fairgrounds (now EUE/Screen Gems Studio). With all that buzz, and acts like Snoop Dogg and Queen Latifah scheduled to perform, Freaknik 1994 drew a record 200,000 attendees—70,000 of whom turned out for a Saturday concert in Piedmont Park.

Jefferi Lee spent a decade as network operations manager for Black Entertainment Television (BET), which broadcast live from Freaknik. He now runs WHUT-TV in Washington, D.C. For hip-hop and black music, it became a mecca. Freaknik was bigger than the MTV Video Music Awards. When the corporate sponsorship showed up, it was huge.

Kasim Reed: I think that Freaknik was a good thing—until it wasn’t, until it lost its essence. It stopped being about black students having a good time and took on an All-Star Game type of feel. It really became a black Daytona Beach.

PHOTOGRAPH BY SHELIA TURNER

Sonia Murray: By the time Freaknik reached its height, for a record label it was an opportunity. You were getting your target audience gathered all in one place. A lot of labels had events and parties, and labels saw it as an opportunity to promote their new artist. You’d see the posters everywhere, all up and down the telephone poles. I remember Diddy coming down. I remember seeing Snoop. That wasn’t the era of VIP. You could see people at events and be around them. I remember Jermaine Dupri. It was his city; he was everywhere.

Jermaine Dupri: Me and Kris Kross went to the mall during Freaknik, and the mall damn near got shut down. That was like an advertising, marketing thing. That also created the mindset for people that they’re going to run into people at the mall; they’re going to see famous people.

Dallas Austin was a producer/songwriter working with artists including TLC, Brandy, Monica and others during the Freaknik era. A College Park native, he still lives in Atlanta. I remember one year seeing Outkast … a lot of different people. At times we just went, and we all saw each other at Piedmont Park. It was almost like a festival with the concerts—different people were doing different things. But it was never rounded up like a Lollapalooza.

Luther Campbell: If you were an artist promoting any product, it was a great place to party, to promote new music. You could go and meet a lot of beautiful women. It was an event you just had to be at.

Ryan Cameron: It was the heyday of LaFace Records. The Dirty South was really starting to come into its own. Freaknik was ratchet before ratchet was a word.

Salah Ananse is an Atlanta DJ and attended Morehouse College from 1991 to 1995. Once it grew, everybody saw it as a money-making opportunity.

Dallas Austin: Freaknik was a good time to book a show because you knew it was going to be packed. Everybody knows a good weekend. Club owners, promoters knew during Freaknik you were gonna make money. So different venues would do stuff on their own to make money. It wasn’t [a coordinated festival] like Music Midtown.

Sonia Murray: On Saturday at Lenox, you could see every artist there. I remember going down the escalator and the guys from Boyz II Men were harmonizing on the escalator going into the food court! It was gigantic for the malls. This was when a lot of record labels were talking about designers for the first time. Hip-hop’s transition into that label-dropping kind of music. People were going out and buying those things, wearing them in the videos. It was all moving in tandem with the music and the scene at that time.

Jermaine Dupri: I was driving during this whole era. I didn’t want a driver. I wanted to get in my Range Rover and drive. Madeline Woods from BET came to Atlanta and I was like, “Yo, I’m going to take you out and show you what’s going on at Freaknik.” We were stuck in traffic. I was driving and people knew her because she was on TV and it was like the craziest shit in the world! I took Larenz Tate to Club 112 that night … this was when Menace II Society had come out. Club 112 was so crowded that I couldn’t even go through the front of the club; I had to go through the kitchen. That’s when I knew Freaknik had taken over the city.

Luther Campbell: Being the owner of my record label, I could monitor record sales. I knew where the music was playing, where it was being sold, what’s getting people excited. We would look for events like Freaknik to be a part of. Once we realized that, “Hey man, this is what people want,” it was like, “Okay, let’s own it.” People in Atlanta loved us, and we loved Atlanta.

The video for Playa Poncho’s “Whatz Up, Whatz Up,” was shot near the Civic Center during Freaknik 1995 and was the first installment of the So So Def Bass All-Stars project. “We shot that video around the same time as Freaknik because there were so many people in town. That song embodies the look of Freaknik,” says So So Def founder Jermaine Dupri.

Chapter IV. The Tide Turns

While the music business profited, others saw Freaknik as a liability. In April 1995, restaurants announced plans to close, and some hotels refused to take reservations. For the first time since 1936, Atlanta’s Dogwood Festival was rescheduled. Some 600 residents and businesses formed the Freaknik Fallout Group and threatened to sue the city. The Wall Street Journal reported that Campbell approached his counterpart in New Orleans to discuss a Freaknik relocation. Meanwhile, a group of AUC students and alumni put together yet another alternative—FreedomFest.

Angelo Fuster: There was pressure from the Chamber of Commerce, from the Convention and Visitors Bureau, from the World Congress Center. There were a couple of conventions taking place. They said their guests would never come back. There was a great deal of pressure that if it can’t be managed better, it needs to stop.

Sharon Toomer: It became a logistical nightmare.

The city budgeted $1 million for security and cleanup, triple what it had spent in 1994. APD and state troopers implemented an aggressive traffic control plan, blocking highway exits and setting up barricades in popular cruising areas. Campbell and his police chief, Beverly Harvard, enlisted the AUC college presidents to send letters to their peers at 140 schools, asking them to discourage students from attending. This thwarted some, but hardly all. On the third weekend in April, 100,000 partyers arrived.

Sharon Toomer: The city made things worse. Their strategy was to make it so unbearable that people didn’t want to come back, and that strategy failed.

Ayanna Brown: By 1995, you had the airport locked up. People were coming from everywhere. So the tone of Freaknik started to change. I can remember seeing middle-aged men in their cars and thinking, “Why are you out here?”

Salah Ananse: Things that went on in strip clubs were spilling out into the streets. Even Mardi Gras is more controlled.

PHOTOGRAPH BY SHELIA TURNER

Kwanza Hall: I came home a couple of times from college to go to Freaknik. I met up with some friends and drove from D.C. once. It changed more and more as I came back. It got worse and worse and worse in terms of the behavior and what [the city] could manage. It got further and further away from college.

Patti Puckett Ghezzi: I was on the Connector; it was super congested. In front of me were these girls riding in a really shiny, fancy car. They were all dressed in the Freaknik outfits of the day—the tight denim shorts. They were lounging like they were sunbathing. Their hair was all done perfect, real pretty girls. They were just the picture of Freaknik—the way the AJC wanted us to frame it.

An ambulance came up behind me, and I immediately started trying to move my car over. I moved to the right; the car in front of me didn’t move at all. Finally, this paramedic got on her loudspeaker and said, “There is a man having a heart attack, and he’s gonna die.” The girls looked at her, shrugged, looked back, and whispered to the guy driving and just refused to move. Right then, I turned on Freaknik. I thought it was something we were tolerating—that the city, or somebody, needed to get under control. But after that I saw it differently. I remember dreading it.

Edward Simpson: I remember being at that BP station next to the West End mall, hanging out in the car, and hearing gunshots ring out and the cars speed by and everybody running for cover. Something like that will stay with you forever.

Angelo Fuster: One night, I went up to the mayor’s office, and we were on the office balcony looking at Mitchell Street, and there was a crowd going in the direction of the State Capitol, and there were shots fired. Everybody dropped to the ground, the mayor’s security detail, everybody. Later that night, there were reports of a group going to Underground and breaking into the Nike store.

Freaknik 1995 wrapped up with grim reports. The rape unit at Grady Memorial Hospital treated 10 victims—far more than in a typical weekend. Police made at least 93 arrests and revelers looted stores in Underground Atlanta and Greenbriar Mall. Three people were shot. Interviewed by Jet magazine, police chief Beverly Harvard said the lewd behavior made her “mad as hell.” Mayor Campbell had had enough, declaring, “Quite frankly, I am absolutely tired of this issue.” City Hall’s solution: strangulation by bureaucracy. In April 1996, Freaknik became a dry run for Olympics traffic control. APD put 1,500 officers on 12-hour shifts, and the city tested its high-tech traffic system. The Georgia Emergency Management Agency opened up its command center, and Georgia National Guard troops drilled at metro-area armories.

Kasim Reed: It would’ve been hard and complex to deal with, as it was for Mayor Campbell. Freaknik had to be ended. It literally metastasized.

Sharon Toomer: It had to go. There’s no way that anyone with any sense can endorse the objectification of women, the criminal element. That had nothing to do with the solid, good intent of Freaknik. Anyone over the age of 22 had no business at Freaknik.

Markel Hutchins was a student at Morehouse College from 1995 to 2000. He is currently a minister and activist living in Atlanta. By the time I got to Morehouse, especially after my second year, it had really turned into a dramatic display of debauchery that undermined the very essence of what the AUC schools meant for this community and really for the nation.

Doug Monroe: The city finally came up with a way to frustrate the students to the point where they did not want to come back. You can’t just shut down the city because of the need to get places. Once they started managing it the way they did, it took away a lot of the fun of when it was a big crowd. A lot of people came for the stopping in traffic, partying, meeting people in the street. It was sort of pointless after that.

Joe Spillane: Whenever you take a group of people that want to cruise the streets in a certain pattern, when you disrupt the pattern; that makes it less fun. I think it does naturally kill the vibe. At the time I was a lowly sergeant, so I can’t tell you what the intent was, but I think when the mayor said, “Enough is enough,” I think that became the intent. If you think about it, the streets of Atlanta weren’t designed for cruising. They’re designed to go to a destination and leave a destination, but not to drive up and down. There’s not enough surface to allow that many cars to continuously do that without serious implications to the city.

Chris Williams: Cops were showing up [at Lenox] and people weren’t doing nothing; they were just there. It was amazing how differently they looked at us, like we weren’t college educated, like we were thugs. We were rocking Polo, Tommy Hilfiger. We weren’t looking raggedy. We had money to spend!

Ryan Cameron: Bill Campbell was given the name “the Mayor Who Killed Freaknik.” People felt like they were no longer welcome.

Chapter V. Death Throes—And a Failed Resurrection

By 1997, Atlanta had posted nearly 300 “No Cruising Zone” signs throughout the city— but mostly downtown, in Buckhead, and near parks. Another strategy was to close surface streets, or to make some streets one-way only. The city also tried to work with students to organize programs like job fairs, adding a sheen of respectability. Sharon Toomer, one of the original picnic’s organizers, and Suzanne Guy Mitchell, who’d taken part in early Freakniks as a Spelman student in the 1980s, submitted a proposal to City Council that outlined a new incarnation of Freaknik, with corporate sponsorships, a website with centralized information (including do’s and don’ts), and designated cruising and 24-hour party zones.

Sharon Toomer: Suzanne crafted a sponsorship and offered it to Coca-Cola. But the city did not go for it.

PHOTOGRAPH BY SHELIA TURNER

City Council and Mayor Campbell adopted one of Toomer and Mitchell’s ideas: A website with information for would-be attendees. The city again tried to re-brand the gathering as Black College Spring Break. Others seized the idea of getting into still-nascent cyber promotion. A commercial site, freaknik.com, drew 13 million pageviews between January and April, 1997, and included recorded messages from Atlanta celebrities ranging from Atlanta Falcons star Andre Rison and New Edition’s Michael Bivins to Dexter King, who admonished the youngsters to “have a good time … be safe and stay positive.”

Freaknik 1997 drew near and antsy Atlantans had another cause for concern: Rumors of a bomb threat. Because the weekend coincided with the anniversary of the botched April 19, 1993 raid at David Koresh’s Waco compound and the 1995 bombing of a federal building in Oklahoma City, federal agencies warned that minority groups could be targeted on so-called “Militia Day.” Federal agents joined the already on-alert local police to prepare for Freaknik, and Atlantans, still shaken by the bombing during the 1996 Summer Olympics, hunkered down at home.

The event itself was deemed dull. Partiers stayed away and police patrolled aggressively. Two incidents exacerbated race and class tensions. On Freaknik weekend, a young Atlanta father, Timmie Sinclair, was stopped by cops after going through a Freaknik traffic barricade. Sinclair said other police told him to go through, as he was heading out to get medicine for his child. But officers beat and pepper-sprayed Sinclair, and the episode was captured on video by a Freaknik attendee. On the flip side, a convention of 10,000 employees of TruServ hardware stores was so disrupted during Freaknik, that the company threatened to cancel future meetings in Atlanta, meaning the city would lose an estimated $18 million economic impact. While the NAACP and others civil rights groups protested aggressive policing and the “Sinclair Incident,” the business community frothed at the prospect of losing more big conventions.

In his 1998 bestseller A Man In Full, journalist and social observer Tom Wolfe opened with a scene set in Freaknik, that, like the rest of his novel, highlighted racial and economic tensions in Atlanta. “These black boys and girls came to Atlanta from colleges all over the place for Freaknik … and here they were on Piedmont Avenue, in the heart of the northern third of Atlanta, the white third, flooding the streets, the parks, the malls, taking over Midtown and Downtown and the commercial strips of Buckhead, tying up traffic,” wrote Wolfe, describing students “baying at the moon, which turns chocolate during Freaknik, freaking out White Atlanta, scaring them indoors, where they cower for three days, giving them a snootful of the future …”

The year Wolfe’s novel was published, a biracial committee of business and civic leaders studied Freaknik. Their recommendation to the mayor: Shut the event down. George Hawthorne, committee co-chair, told the AJC that Freaknik was dominated by “a criminal element of sexual abuse against women. It’s time to make a change.” Columnist Cynthia Tucker called out the mayor for not opposing Freaknik. “The committee headed by Hawthorne, an African American businessman, gave Campbell any political cover he needed,” she wrote. “The committee’s report underscored what was already clear: Freaknik does not enjoy the unqualified support of African Americans—at least not those of us who have hit middle-age.” In 1999, mayor Campbell appointed a panel to plan future Freakniks. One of the student members was Markel Hutchins.

Markel Hutchins: The general framework was, I think, mayor Campbell was trying to toe the line between making certain that people had the right to assemble or people felt comfortable, but also making certain that public safety and property was protected and that the streets were not in total chaos and pandemonium. There may have been 10 or 12 of us. We had a direct line of communication to the mayor and chief of police. We were to serve as the eyes and ears for the mayor’s office, the city government, and law enforcement. We were also tasked with the responsibility of giving a public voice for what this redefinition and identification of black college weekend was all about.

By 1999, crowds dwindled to around 50,000—a shadow of Freaknik’s former glory. And the police pressure stepped up, with 350 arrests and thousands of citations issued. By 2000, Freaknik had fizzled, and students went to Galveston and Daytona Beach.

PHOTOGRAPH BY SHELIA TURNER

Patti Puckett Ghezzi: It got real pathetic. The cool people had moved on. There was this woman—way too old to be a student—who was dancing on her car, with nobody there to watch her. [A reporter] walked over to her and was like, “What are you doing?” She said, “It’s Freaknik, and I’m shaking my tail!” It was so tragic. To me, that was just like the sign that it was so over.

Markel Hutchins: I resigned [from the committee] because I got to the point where I’d become frustrated by the lack of progress. In terms of police officers and law enforcement making a more intent effort on not profiling, not harassing and not mistreating the young people that came. But I also was very frustrated because the efforts to reimagine and redefine Freaknik into black college weekend had such marginal success that it was rather frustrating to be a part of that process.

Derrick Boazman: At the point that Freaknik terminated it was reprehensible. If I was to rate it in the lexicon of black life, I’d say it’s better forgotten than esteemed and remembered.

In 2010, Atlanta-based rapper T-Pain starred in Adult Swim’s “Freaknik: The Musical,” a cartoon about a rap group’s journey to Atlanta to attend a revived version of the legendary party. Other stars who loaned their voices to the effort included Snoop Dogg, Lil Wayne, Big Boi, Rick Ross, and Cee-Lo. The animated version imagines “The Spirit of Freaknik” as a gold chain-wearing ghost from another galaxy. In the opening scene, Lil Jon predicts that the party could rise again: “They killed Freaknik. Or at least that’s what they thought they did … They were able to ruin the party, but they couldn’t kill the soul of Freaknik. They say it lives on, waiting to return.”

For now, however, Freaknik lives on primarily as a subject of academic study, and in that arena continues to spark debate on issues of race and class. In a 2004 paper, Georgia State University communications professor Marian Meyers analyzed media coverage of Freaknik and concluded that news outlets tended to cast women as “jezebels” deserving any violence that occurred while it “criminalized black men primarily with respect to property damage while decriminalizing them concerning their abuse of black women. The safety of black women appears of less consequence than that of property.” In a 2012 thesis, Peter Stockus positioned the event as a form of political protest, arguing that students claiming the streets of Atlanta could be “seen in the same tradition of acknowledged forms of racial discourse such as slave rituals of resistance and the civil rights movement.” Freaknik is referenced in scholarly articles and books on everything from Atlanta’s transportation system to residential segregation patterns.

PHOTOGRAPH BY SHELIA TURNER

Kasim Reed: All in all, I’d say Freaknik was a net positive for the city of Atlanta. Freaknik was an important part of cementing Atlanta’s role as a center of black culture. When you think about the role Atlanta has in the minds of black people in America, Freaknik played a role in creating that brand.

Sam Massell: There were pluses and minuses, but the minuses outweighed the pluses. The fear factor can’t be dismissed. You don’t want your citizenry to ever be scared to go outside, to work, to school because of some group that’s in town for a meeting. The pluses were introducing the city to new people. I bet a number of those people who were involved in Freaknik now live in Atlanta. They came here to find a life that they thought would be the quality they would enjoy.

Jermaine Dupri: I introduced a lot of people to Atlanta through Freaknik. In “Welcome to Atlanta,” when I wrote, “Where people don’t visit/They move out here,” that’s from me watching people come for Freaknik. They would come here and be like, “I love this place!” They had never seen this many black people have a good life in a place like this. Back then, it was good for a black person to move to Atlanta.

Salah Ananse: It was a fun era in Atlanta life, but I’m not looking back on it like, “I want that back.”

Kasim Reed: It wouldn’t work today. Freaknik is just going to be something that’s ours, that’s in our memories. We had our run.

Jermaine Dupri: If you take all that stuff and you look at it now and you replay all the tapes, you say, “Look at all of you guys leaving our city, thinking what was coming was negative.” It was not a negative. Freaknik was just like hip-hop in every aspect: It was something that was created by the youth. It became something that you could make money off of. It became something you could market your business to. It became something that was looked at as a bad thing, but it wasn’t. I hate that it’s gone.

Ryan Cameron: That’s what makes nostalgia, nostalgia. You can Google it all day, but I’m a witness. I know what it was like. You can try to recreate it all you want to, but it’s just not going to be the same.

About the Photographs

The series of black-and-white photographs from Freaknik 1994 are by shelia turner/Atlanta. A narrative documentary photographer, she uses photographs to provide a platform for the examination of US life and culture. More at sheliaturnerprojects.com

The series of black-and-white photographs from Freaknik 1994 are by shelia turner/Atlanta. A narrative documentary photographer, she uses photographs to provide a platform for the examination of US life and culture. More at sheliaturnerprojects.com

No comments:

Post a Comment